Saturn’s small, gleaming moon Enceladus has once again taken center stage in the search for habitable environments beyond Earth. A new analysis of data from NASA’s Cassini mission — re-examined years after the spacecraft plunged into Saturn’s atmosphere — reveals that complex organic compounds are emerging directly from the moon’s subsurface ocean. The findings provide the clearest evidence yet that Enceladus hosts a chemically rich environment capable of supporting prebiotic reactions, and possibly life itself.

A Window Into a Hidden Ocean

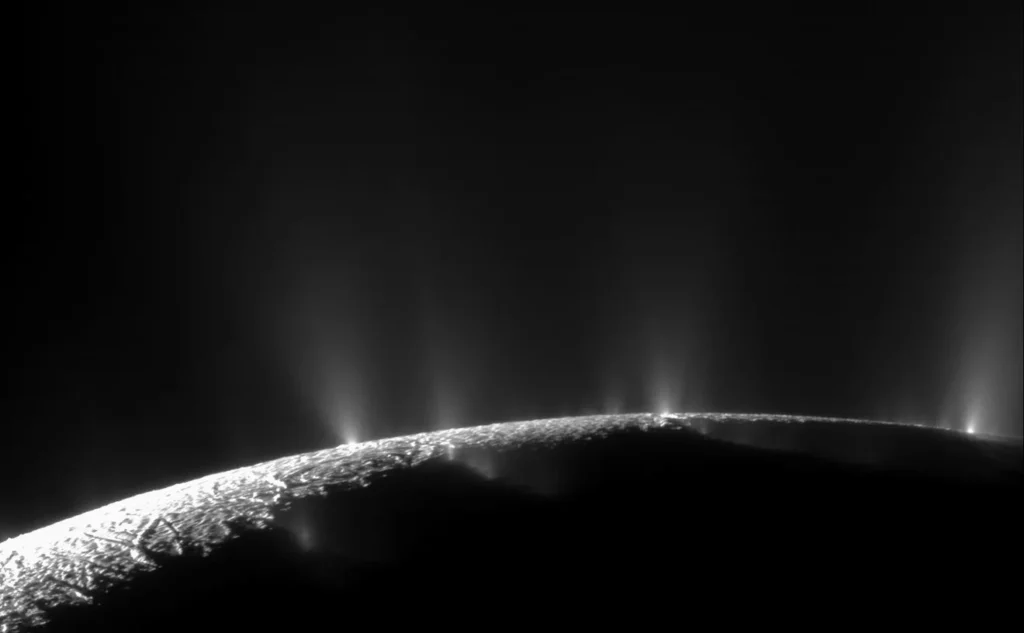

Enceladus is only about 500 kilometers across, yet it harbors a global ocean beneath an icy crust. At its south pole, spectacular fissures known as “tiger stripes” vent plumes of water vapor and ice grains into space. During a close 2008 flyby, Cassini passed directly through this erupting spray at a velocity of roughly 18 kilometers per second, allowing its onboard instruments to sample grains as they burst apart on impact.

The recent study focuses on these “fresh” grains — particles released from the ocean just minutes before Cassini intercepted them. Because they’ve had little time to be altered by radiation or chemical reactions in space, they offer a uniquely pristine snapshot of the chemistry taking place beneath the ice.

A Suite of Complex Organic Molecules

Mass spectrometry measurements from Cassini’s Cosmic Dust Analyzer show an unexpectedly diverse set of organic fragments. Researchers identified signatures of:

- Aliphatic hydrocarbons, which are the building blocks of many biologically relevant molecules.

- Cyclic and heterocyclic compounds, some containing nitrogen or oxygen.

- Ethers, esters, and alkenes, indicating a mixture of functional groups that rarely form without active chemistry.

- Oxygen- and nitrogen-bearing organics that may trace back to processes near the ocean floor.

These detections meaningfully expand the known chemical inventory of Enceladus. Previous studies of particles in Saturn’s E ring — composed partly of older, recycled plume grains — showed simpler organics, but their long exposure to space made their origin uncertain. The new analysis confirms that these molecules are not the product of radiation or external contamination; they arise directly from the moon’s interior.

Implications for Habitability

The presence of such a varied organic mixture suggests that the subsurface ocean is not a static reservoir. Instead, it appears to be a dynamic system where water, rock, and heat interact — conditions reminiscent of Earth’s hydrothermal vents, which teem with life.

Evidence from earlier Cassini studies has already hinted at hydrothermal activity: dissolved salts, molecular hydrogen, silica nanograins, and even phosphates have all been detected in the plumes. Combined with the newly identified organics, the picture becomes clearer: Enceladus meets many of the key criteria for habitability.

Though the new findings stop short of indicating biology, they contribute to a rapidly strengthening case that Enceladus possesses the right ingredients, energy sources, and chemical complexity to support life.

Rewriting the Priority List for Exploration

Enceladus is now one of the most compelling destinations for astrobiology. The results underscore the need for a dedicated mission capable of performing high-resolution compositional measurements — or even returning samples to Earth. Future spacecraft could fly repeatedly through the plumes, land near active vents, or deploy instruments designed specifically to distinguish between abiotic organic chemistry and true biosignatures.

With Cassini’s mission complete, the moon continues to reveal new secrets from the archives of its long-lived data. What was once a remote, icy outlier in the Saturnian system now stands as one of the most promising places in the Solar System to search for life.