Understanding Re-entry, Hypersonic Flight, and a Fatal Chain of Events

On February 1, 2003, NASA lost Space Shuttle Columbia (STS-107) and its seven-member crew during atmospheric re-entry. While the immediate cause was damage to the shuttle’s left wing sustained during launch, the ultimate failure unfolded through the unforgiving physics of hypersonic flight and re-entry heating.

This article breaks down the technical and physical principles behind the Columbia disaster—from ascent dynamics and foam impact to plasma flow, heat transfer, and structural collapse—offering a clear, science-focused explanation of why the accident was inevitable once damage occurred.

Space Shuttle Ascent: Speed and Conditions at 80 Seconds

During launch, the Space Shuttle accelerated rapidly under the thrust of its Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs).

At approximately 80 seconds after liftoff:

- Velocity: ~700–900 m/s (≈ Mach 2–3)

- Altitude: ~20–30 km

- Flight phase: Just past Max Q (maximum aerodynamic pressure)

This timing is critical. During STS-107, a piece of foam insulation separated from the external tank around 81 seconds after launch, striking the shuttle’s left wing leading edge. At these speeds, even lightweight foam carries significant kinetic energy, enough to damage fragile thermal protection materials.

Breaking: NASA Troubleshoots Artemis II Upper Stage Issue — Preparing to Roll Back

NASA’s Artemis II Mission Advances Toward March 6 Launch After Successful SLS Wet Dress Rehearsal

£1 Million Boost for Arts and Humanities Research into Outer Space

SpaceX’s New Moon-First Strategy: A Groundbreaking Pivot in Lunar and AI Infrastructure

Artemis II Trajectory Explained: How NASA Will Send Humans Around the Moon Again

Beyond the Moon: Lesser-Known and Fascinating Facts About NASA’s Artemis II Mission

Artemis II: Key Questions About Humanity’s Next Crewed Lunar Mission

Space Park Leicester Launches “Executive Guide to Space” Mission Programme

Behind the Columbia Space Shuttle Disaster

NASA’s Artemis 2 Mission: Everything You Need to Know About the First Crewed Lunar Flyby of the Artemis Era

The Space Shuttle Challenger Disaster: Causes, Consequences, and Lessons Learned

The Apollo 1 Disaster: A Tragic Turning Point in Spaceflight Safety

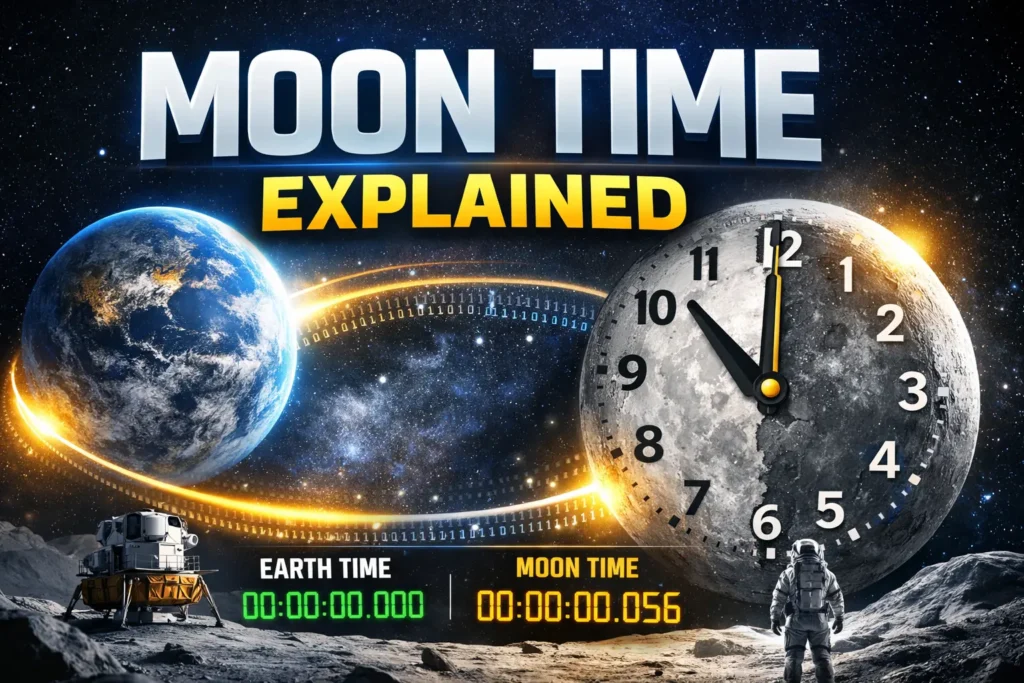

Moon Time: Why the Moon Has Its Own Clock and Why It Matters for Future Exploration

Artemis II: What’s about

Foam Impact and Thermal Protection System Damage

The shuttle’s Thermal Protection System (TPS) was designed to withstand extreme temperatures during re-entry—but only if it remained intact.

Key TPS components:

- Silica tiles (belly and fuselage):

- Lightweight, highly insulating

- Rated to ~1,260 °C

- Reinforced Carbon-Carbon (RCC) panels (wing leading edges):

- Rated to ~1,650 °C

- Strong under heat, but brittle and impact-sensitive

The foam strike damaged one or more RCC panels on Columbia’s left wing, creating a breach that would later prove catastrophic.

The Physics of Atmospheric Re-entry

Re-entry velocity and energy

A shuttle returning from orbit travels at approximately:

- 7.8 km/s (≈ 28,000 km/h, Mach 25+)

The challenge of re-entry is not friction alone, but energy dissipation. The vehicle must shed immense kinetic energy without allowing heat to penetrate its structure.

Why Re-entry Generates Extreme Heat

Contrary to popular belief, re-entry heating is not primarily caused by friction.

Instead, it is driven by adiabatic compression:

- At hypersonic speeds, air cannot move out of the way fast enough

- Air molecules compress violently in front of the vehicle

- Compression raises temperatures to 1,500–1,650 °C

- A bow shock forms, creating a plasma sheath around the spacecraft

A properly shaped vehicle keeps this superheated gas away from its surface. The shuttle’s TPS was essential for maintaining that separation.

Plasma Intrusion and Structural Failure

Due to the damaged RCC panel:

- Superheated plasma entered Columbia’s left wing

- Internal aluminum structures (melting point ~660 °C) began to fail

- Temperature sensors inside the wing recorded abnormal heat increases

- Structural weakening caused asymmetric lift and drag

At hypersonic speeds, even small asymmetries produce large aerodynamic forces. As the left wing deteriorated:

- Flight control systems overcompensated

- Control authority was eventually lost

- The shuttle broke apart under aerodynamic stress

By the time telemetry was lost, the failure was already irreversible.

Why the Shuttle Could Not Be Saved

Once plasma breached the wing, there were no recovery options:

- No redundancy in the heat shield

- No capability to slow down or alter re-entry physics

- No crew escape system at hypersonic velocity

Re-entry physics allows zero tolerance for structural flaws. Even millimeter-scale damage can cascade into total vehicle loss.

Lessons from Columbia

The Columbia disaster was not solely a materials failure—it was a systems failure involving:

- Normalization of risk (foam shedding was known)

- Insufficient on-orbit inspection capability

- Organizational barriers to escalating safety concerns

In response, NASA implemented:

- On-orbit damage inspection tools

- Heat shield repair techniques

- Cultural reforms prioritizing dissent and safety

These lessons directly influenced the decision to retire the Space Shuttle program in 2011.

Conclusion

The loss of Columbia demonstrates a harsh truth of spaceflight:

Hypersonic physics is unforgiving. Small defects become fatal, and once re-entry begins, there is no margin for error.

Understanding the physics behind the disaster honors the crew by ensuring their loss continues to educate engineers, scientists, and space enthusiasts worldwide.